Connected Care: An IoT Haptic Baby Monitor

Year

'25

Client

Course project

Service

Circuit Design, Cloud Pub/Sub Architecture, Autodesk Fusion

This project explores the concept of remote non-verbal communication. I built a functional "Digital Ecosystem" that translates a baby’s physical status—heartbeat, movement, and cries—into a remote sensory experience for the caregiver.

Unlike traditional monitors that just stream video, this device uses haptic feedback and real-time data visualization to create a tactile connection between parent and child.

Background

We began with a simple question: How can we share our needs when words aren't possible?

Babies speak a language of tiny movements and soft cries. We wanted to design a system that respects this universal need to be heard. The goal was to move beyond passive observation (watching a screen) to an immersive experience where a parent can "feel" the baby's status. While designed for infants, this foundation of universal connection speculates on future applications for elderly care or remote medical support.

Tasks

My primary challenge was to build a complete Internet of Things (IoT) system from scratch with no prior microcontroller experience.

The specific objectives were:

Input: Capture real-time data for heart rate, sound intensity, and physical movement.

Connectivity: Establish a cloud communication loop to transmit data between two separate physical devices.

Output: Translate raw data into meaningful feedback (visual text and haptic vibration) on a receiver device.

Actions

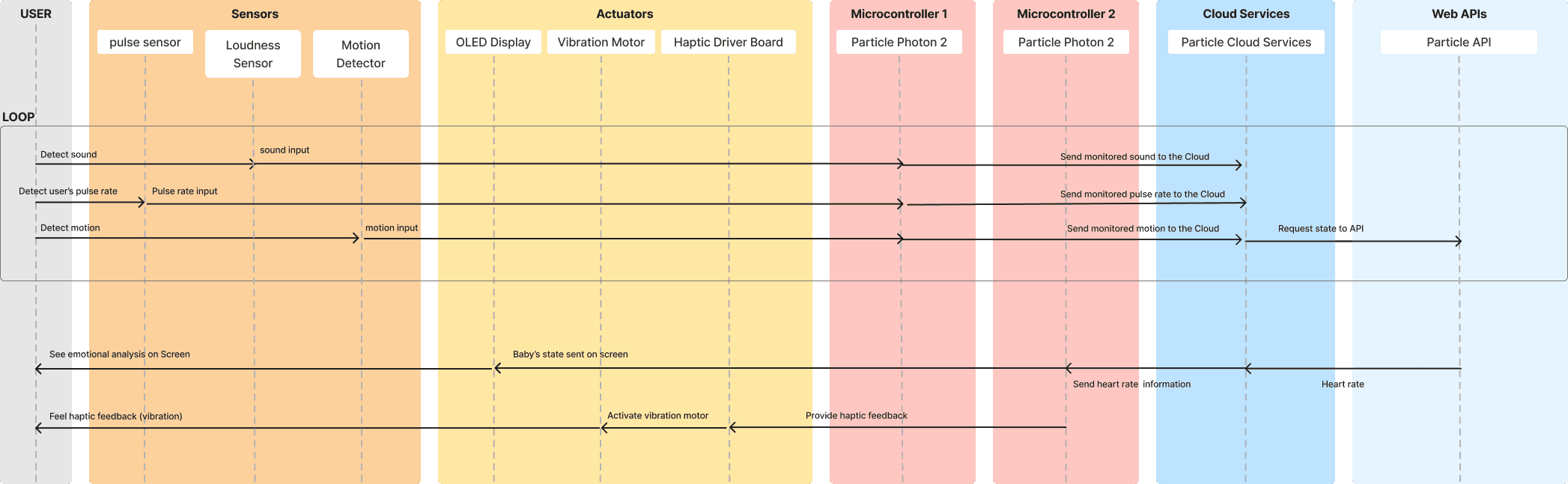

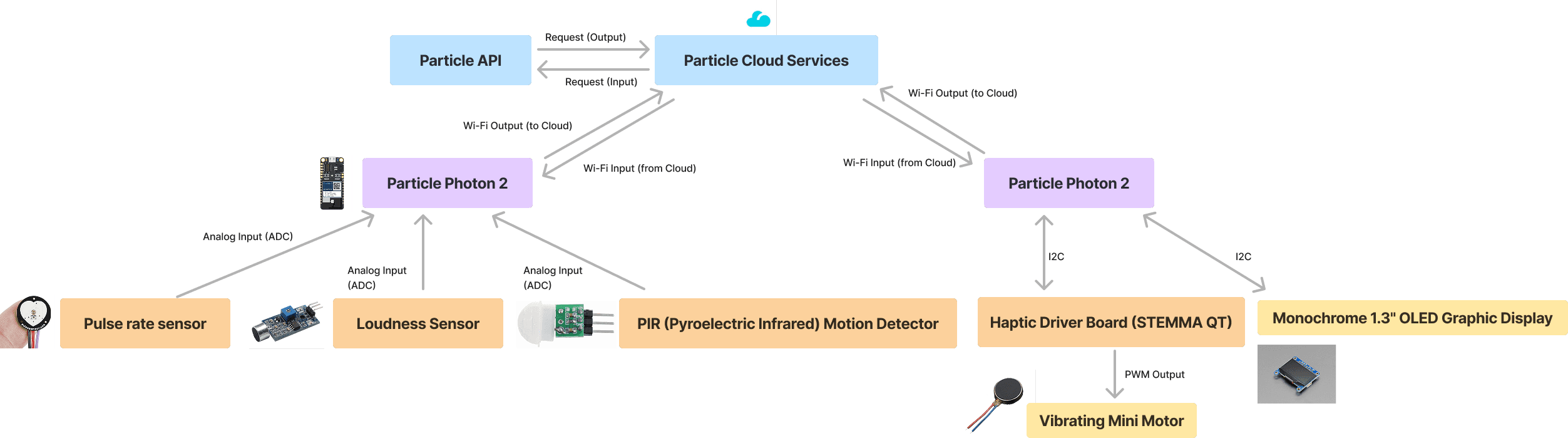

To build this digital ecosystem, I engineered a "Sender" and "Receiver" architecture using two Photon 2 microcontrollers.

Step 1: Sensor Integration (The Sender)

I wired the input sensors to the first microcontroller. This required calibrating the sensitivity of the sensors to distinguish between background noise/movement and actual events (e.g., a baby crying vs. ambient room noise).

Pulse Sensor: Captures BPM (Beats Per Minute).

Loudness Sensor: Detects crying intensity.

PIR Sensor: Monitors physical activity.

Step 2: Cloud Architecture

Using the Particle API, I programmed the "Sender" device to publish sensor readings to the cloud loop continuously. This allowed the data to exist independently of the hardware, a crucial step for remote monitoring.

Step 3: Feedback Loops (The Receiver)

I programmed the second device to "subscribe" to these specific cloud events.

Visuals: I utilized a Monochrome 1.3" OLED display to render the data in real-time (e.g., displaying "Movement Detected" or specific BPM).

Haptics: To create an emotional connection, I integrated a vibrating mini motor. When specific thresholds were met (high loudness or motion), the device triggers a vibration, allowing the parent to be alerted physically without looking at a screen.

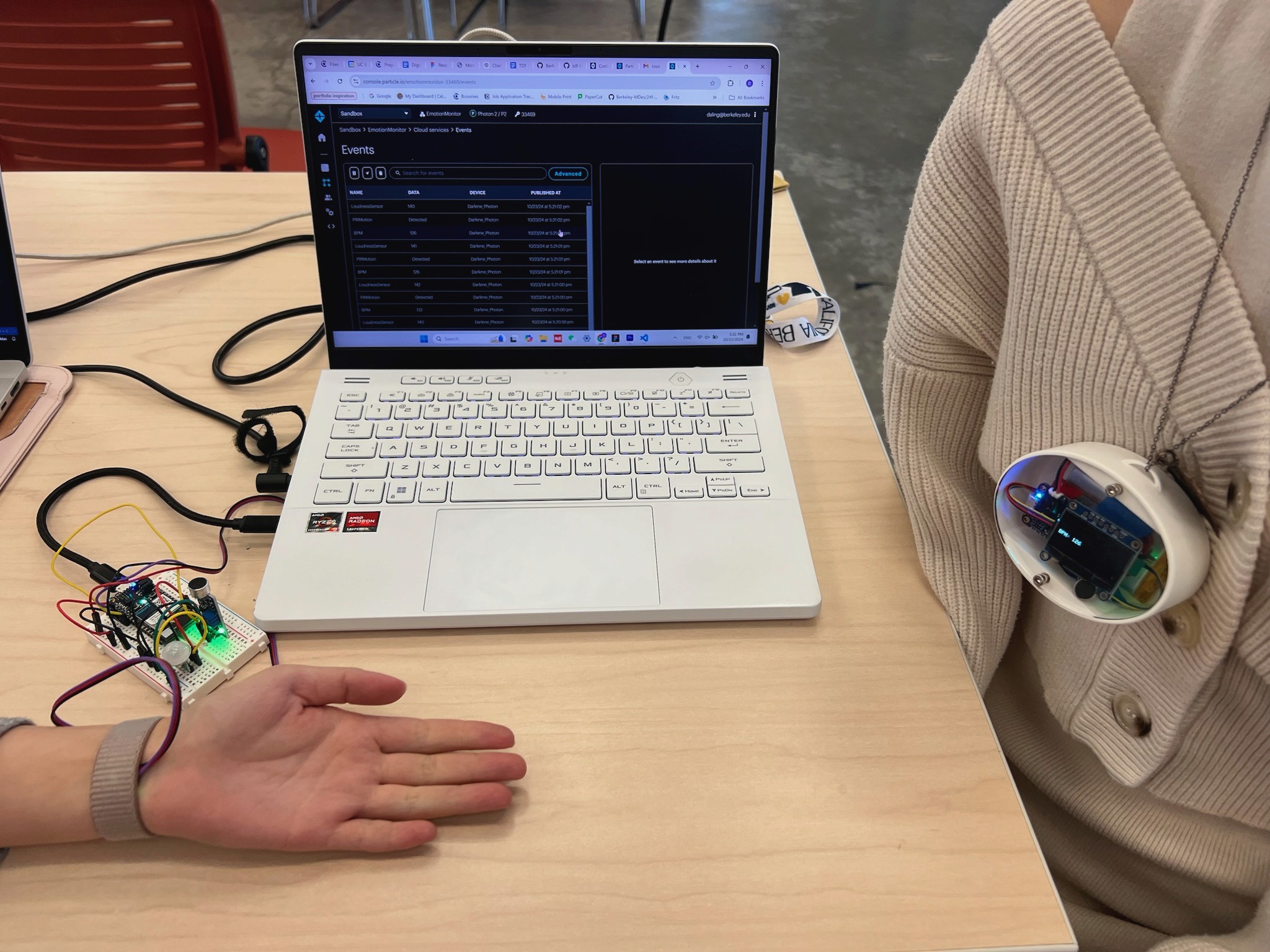

Step 4: Iterative Debugging

The process involved significant troubleshooting. For example, converting raw pulse data into a stable BPM reading required multiple code iterations. I also had to learn to distinguish between hardware failures (loose wiring) and software logic errors.

Outcome

The final prototype is a fully functioning Digital Ecosystem.

Real-Time Sync: The system successfully transmits pulse, sound, and motion data to the cloud and retrieves it on the remote device with minimal latency.

Multi-Sensory Feedback: Users can see the baby's status on the OLED screen and feel alerts through the haptic motor.

Scalability: The architecture is proven to be adaptable. The same "Pub/Sub" logic used here could be expanded to include AI-driven analysis, such as predicting wake windows or automating nursery environments (lighting/temperature) based on the baby's patterns.

Reflection

Bridging the Hardware-Software Gap

This project was a steep learning curve in technical prototyping. The biggest takeaway was learning how to troubleshoot a hybrid system. When the device failed, I had to learn to isolate the variable—was it the code, the cloud connection, or a physical wire?

Future Speculations

Beyond baby monitoring, this project highlights the potential for adaptable anthropogenic environments.

AI Integration: Future versions could use AI to automate handovers between devices (e.g., dimming lights when a heart rate slows).

Co-Creation: By making these ecosystems transparent, users could customize how they receive care data, redefining "ownership" of medical devices from passive usage to active co-creation.

© Connected Care: An IoT Haptic Baby Monitor